A Songline in the

Elephant Hills

Earthly Rhythms, Cadence, and the Silencing of a Rainforest Landscape

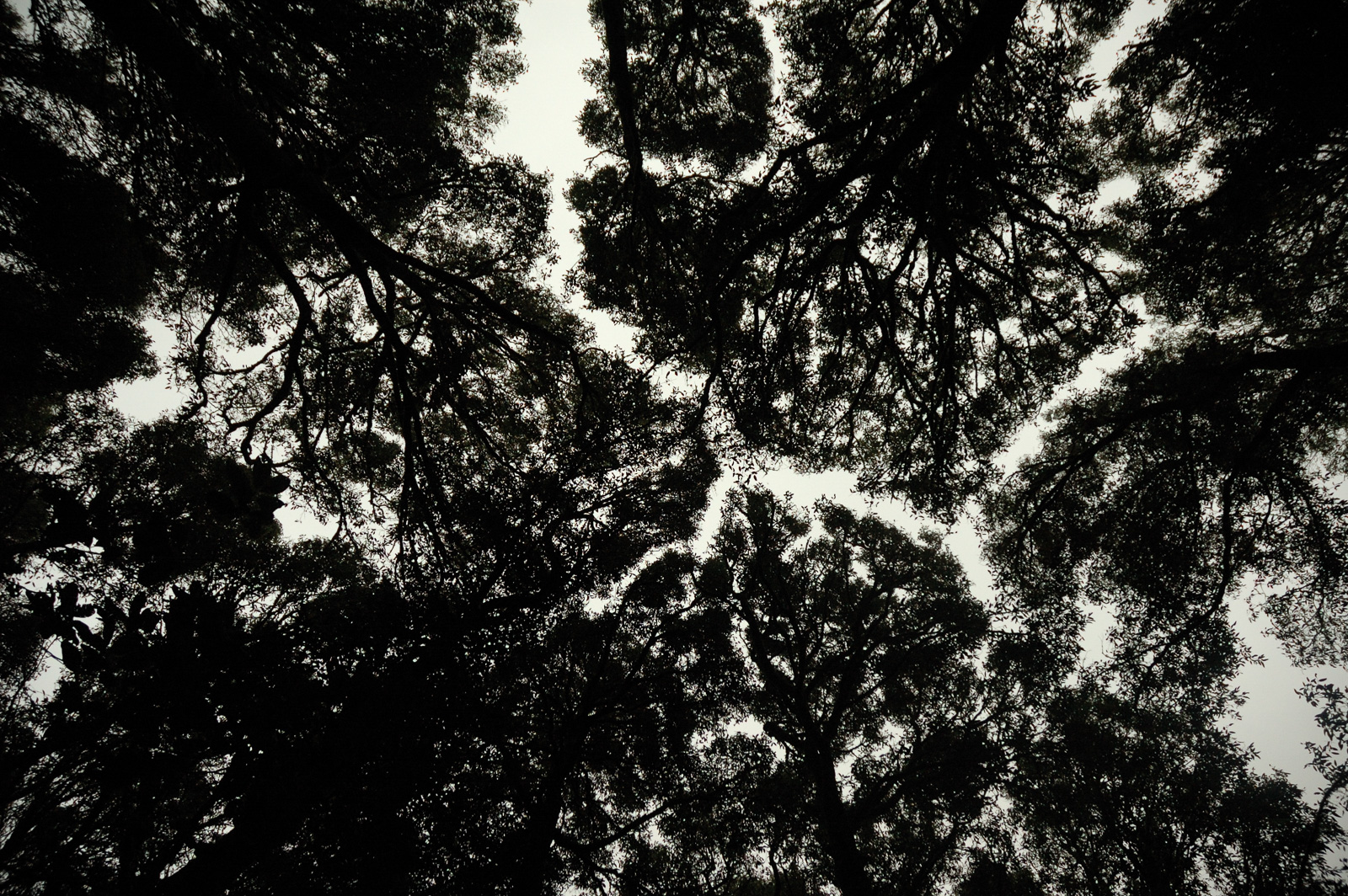

The dawn chorus in a shola in the Anamalai hills

In this essay, we explore the sounds and silences of a tropical rainforest landscape that has been our home for the last quarter of a century: the Anamalai or elephant hills. Taking inspiration from the Australian aboriginal idea of the “songline,” we will describe how the acoustic world formed by the sounds of nature intimately connects us to the land and its ecology, history, and tapestry of lifeforms. The familiar songs and calls of birds define our home in the hills to such an extent that their absence would leave us unmoored. Every year, the sounds that declare the arrival, and the silences that mark the departure, of migrant birds define our seasons to the accompaniment of the orchestra of wind and rain and the dance of sun and clouds. In the rainforest, the symphonies and cacophonies of rainforest creatures register a flourishing and vibrant ecosystem vital to our own well-being and flourishing. The aural world, including the sounds beyond human hearing, is as rich or even richer than the visual. And yet, this is a world at risk of being silenced by many powerful forces of destruction clawing away at the land. In registering our songlines and what they mean to us, we can learn to protect and care for the land and rise to defend it against silencing.

Rainforest Canopy; Photo by Kalyan Varma

“…A musical phrase is a map reference… Music is a memory bank for finding one’s way about the world.”

~ paraphrased from Songlines (1987) by Bruce Chatwin

A cool, silvery-grey dawn breaks over the Anamalai as we nudge each other awake, listening and thinking. Is the whistling-thrush singing?

Outside, mist hangs over a rolling landscape of manicured tea plantations surrounding the hill town of Valparai, our home for the last twenty-five years. We lie awake for a few minutes in the dreamworld between sleep and wakefulness. The stillness of dawn, the shrillness of a couple of crickets, silence. And then, without overture or ado, the serenade begins. Mellow whistles rise and flow, smooth and mellifluous, waxing in through the window, waning into the distant mountains, as if the Malabar Whistling-Thrush is taunting us with song to enter the dreamscape again or draw us out into the sun-gilded morning. There are other birds calling, too: Whooaw! Check-your- charrack-choo! shouts a Grey Junglefowl from the tea plantations, while the Red-whiskered Bulbuls chuckle from the mango tree and the busy tailorbird in the hedge goes pitch-it pitch-it pitch-it to the kutoor-kutoor-kutoor metronome of the White-cheeked Barbet. But it is the lilting, flowing song of the whistling-thrush, the endlessly varying tunes punctuated by a few familiar notes and piercing whistles, that is our morning benediction here in the Elephant Hills.

All is well. I’m still here.

It’s not a benediction that we take lightly. As biologists we’ve spent a quarter century watching the town where we live, the landscape around, and the world itself change around us. The whistling-thrushes have a stronger claim to these mountains as home. Their morning music is as much their conversation with others of their own kind, as it is a songline speaking of intimate connection to the mountains and rivers and land. What if one morning we awoke, in our home, but didn’t hear the melodious song of our neighbour, the whistling-thrush?

Malabar Whistling-thrush; Photo by P. Jeganathan

The landscape of the Valparai Plateau, at first glance, looks much the same as it might have a century earlier, after the colonial wave of land clearing, rainforest burning, and planting had beaten the land into monocultures of tea, some coffee or cardamom, and eucalyptus. The vast tracts of rainforest roamed by timeless herds of elephants had been reduced to vestiges, and the original inhabitants, the Kadar people, were pushed to the margins. Those remnants of rainforest that survived into the turn of the century had drawn us here, as biologists, to study, document, and learn from. And yet, over the last two decades, even as the rainforests persist, they suffer from rising heat, intensifying storms, and sharp pulses of drought wrought by climate change. Great trees fall each year, and even protected rainforests within the Anamalai Tiger Reserve have taken on a tattered appearance. The hornbills roam the landscape questing for nest hollows in the few alien silver oak and eucalyptus trees not yet felled; the intelligent lion-tailed macaques troop down from the trees to scavenge and sift garbage and food waste discarded by tourists and residents.

The tea and coffee plantations, too, are witnessing waves of change. The land’s “owners” and managers come and go, the land changes hands like a commodity. Older residents leave in search of better prospects in the plains, while migrants driven by poverty troop in from elsewhere to fill the workforce vacuums. New pests swarm the crops, undaunted by waves of pesticide attack. The roads grow wider, the vehicles go faster, leaving bloodied animals crushed as roadkill in the wake of development and progress. The hill streams thin out and disappear. The mosquitoes around town grow fatter and more numerous. In the township, the “home stays” that are just multi-storey lodges grow and grow. The old houses and the trees that stood alongside fall and fall. Concrete and tourist vehicles choke soil and street. Slowly, ineluctably, the sounds of birds waver and fade, until their silences now weigh more heavily than their song.

A giant wild jamun tree in the rainforest; Photo by: Divya Mudappa

Attuned to this theatre of precarity and resilience of life around us, we worry about what more the future may bring. It is that worry, coupled with an intention to do what we can to buck the trend, that has motivated our work in this landscape over the last twenty-five years. We work acre by acre with our team to restore degraded rainforest patches in the landscape. The restoration entails removing invasive weeds, freeing up smothered native plants, planting over 150 native rainforest tree species, and tending to the plots for years afterwards to watch over the resurgence of the rainforest. We monitor our efforts and ask: as the rainforests recover, will the forests fill with birds and birdsong again? About two decades into the restoration efforts, we found a heartening pulse of revival in rainforest birdlife in the restored forests as documented by colleagues, some of whom captured the changing soundscape nicely in “Sounds of Restoration,” a short documentary by Project Dhvani. Although richer than in forests that remain degraded, the soundscape is yet to attain the vibrancy and fullness of the mature rainforest. And so we continue our restoration efforts so that the rainforest fragments can sustain or regain some of their diversity, beauty, and sounds of life once again.

A few kilometres away, a different sonic world remains. In the Akkamalai shola, mossy rainforest trees—roped with lianas, festooned with ferns—rise above verdant undergrowth. Here, the dawn breaks in a resounding chorus of birdsong, quelling the nightly orchestra of insects and frogs. The plangent clangs of the Greater Racket-tailed Drongos and the reverberating barks of the Great Hornbill are among the first sounds pulsing through the forest. As the nocturnals fall silent and the sky turns purple to lavender to blue, other birds join the sound fest. Sibilant notes from white-eyes and sunbirds merge with the fluty woodwinds of babblers and fulvettas. Alto whistles of canary-flycatchers counterpoise the becalming basso profundo of emerald doves and imperial-pigeons. As the day progresses, the trill of insects and the buzzsaw of cicadas fill the acoustic space of higher frequencies. At dusk, the nocturnals take over once again—the chucks and hoots of nightjars and owls, the putter and creaks of frogs and tree crickets and other insects, the ultrasound chirps and trills of bats—the shola is never silent. The sounds of water, too, are never far in the shola. A mizzle of rain caressing the leaves one day, a torrent rushing through the canopy in the monsoon, or the endless conversation of rills and rocks every day. The rainforest bequeaths streams and rivers into the Sholayar—the Shola river—bringing water to people in the tea plantations, to Valparai town, and others downstream.

Great Hornbill in flight; Photo by TR Shankar Raman

The aural world, including the sounds beyond human hearing, is as rich or even richer than the visual. The soundscape replete stands as aural testimony to the diversity of the rainforest. The symphonies and cacophonies of rainforest creatures register a flourishing and vibrant ecosystem vital to our own well-being and flourishing.

Back in town, the sounds around our home are a vestige of the rainforest’s sounds, mixed with new voices and human noises. Birds like the Red-whiskered Bulbuls, tailorbirds, and magpie-robins have come to live in the gardens and among people. Drowning their enlivening notes these last few weeks, electric drills roar on one side, pulverising another old building to dust. On the other side, a tile cutter whines in a new six-storey lodge rising dangerously over an old stone retaining wall on the steep slope above us. In the balcony of another nearby lodge, blissfully oblivious to the lost voices and the inescapable noises, tourists gyrate to pop music in front of a Bluetooth blaster.

Fortunately, so far, not everything is just noise. Each day holds promise, too, of sonic serendipity. That loud honk like a truck horn could be the alarm call of a sambar stag warding off a pack of wild dogs in the tea estates. That distant bark that makes us rush out of our home to scan the mountains outside could be a Great Hornbill winging over the tea plantations to one of the rainforest patches in the distance. A few times a month, the thunderous clatter on our metal sheet roof signals another welcome arrival. We quickly close our windows and doors and step outside to watch the troop of lion-tailed macaques come visiting from a neighbouring rainforest fragment. The branches of the mango and jamun trees in our garden crash and heave as they rush about chasing each other, playing, questing for food, and sometimes just blissfully resting. In their forays into these environs, these intelligent primates display a resilience and implicit acceptance of this human-transformed world that holds lessons in accommodation and sharing for us.

Lion-tailed Macaque; Photo by TR Shankar Raman

The sounds both mark and unveil the seasons. A sprightly little ditty from the jamun tree signals the rising fervour of the Greenish Warbler. Smaller than a sparrow, this dull-plumaged migrant spends time among the leaves picking off insects. He’s fattening up and practising his singing voice, in preparation for his great flight to the Himalayas or even further beyond a couple of weeks from now to his breeding territories there, which he will feistily defend with song and spunk. For us, the monsoon will be marked by his silence as much as the autumn and an augury of winter is announced by his return in September.

In the Akkamalai shola, the little White-bellied Sholakilis and Black-and-Orange Flycatchers belie their usually secretive presence by their high-pitched whistling songs as they go about their breeding routines through these warmer months preceding the rains.

White-bellied Sholakili; Photo by Kalyan Varma

In April and early May, as the pre-monsoon thunderstorms arrive with crashing thunder and pouring rain, the earth seems to gain voice and speak up in some of the nearby rainforests. You can stand there among trees, and from beneath the wet soil a rasping cre-kek… cre-kek-ek-ek reverberates underfoot as the subterranean purple frogs sense the rain and prepare for their brief foray above ground to breed. Through the year, the blowing winds, the susurrus of leaves, the splatter and roar of rain act like a constant weather report as we sit cozily in our rooms, sipping coffee or working at our desks.

Purple Frog; Photo by Kalyan Varma

Through long familiarity, the sounds of nature also begin to denote to us not just the voices or presence of other species but also their behaviour. When high-pitched, fast-paced, loud and non-stop chatter and churrs come from the birds outside, we recognise in their panicky notes their mobbing of an owl or alarm at a passing snake or mongoose. The soft coos of the lion-tailed macaques suggest a contact call as one suddenly sets out in quest of a troop member. By night, the little duet the Indian Scops Owls in the garden engage in reassures us that our neighbours are up and about, getting set for their breakfast hunt.

These sounds of nature that we’ve grown accustomed to have become our frame of reference and our tether to our home and our world. They are our songlines of these hills. Their silencing or their loss would be akin to bereavement. Whether they will stay with us or not depends a lot on how we as a community treat nature in our midst and to what extent our actions will erase their presence and voices, replacing them with our noises, our buildings, and our indifference.

Black and Orange Flycatcher; Photo by Kalyan Varma

But for now, as dusk descends on the mountains and dark monsoon clouds gather with portents of rain, the whistling-thrush regales us with song. It is time for us to step out on our work as we’ve been doing for the last quarter century. We will head to our rainforest plant nursery to pick the saplings to plant this year, to raise another rainforest patch where the birds can sing and sing again.